Following on from my note that I intend to do a number of less expansive contributions here, this is another post that does little more than draw attention to an interesting article from the earliest years of television. Researching pre-war adaptations of specific theatre productions of Shakespeare, I was intrigued to discover a 1937 review of scenes from Macbeth with Laurence Olivier. This anonymous response highlighted questions about television, theatre and the cinema that continue to pre-occupy those of us engaged by broadcasts of plays on television and for the likes of NT Live and RSC Live from Stratford-upon-Avon.

Following on from my note that I intend to do a number of less expansive contributions here, this is another post that does little more than draw attention to an interesting article from the earliest years of television. Researching pre-war adaptations of specific theatre productions of Shakespeare, I was intrigued to discover a 1937 review of scenes from Macbeth with Laurence Olivier. This anonymous response highlighted questions about television, theatre and the cinema that continue to pre-occupy those of us engaged by broadcasts of plays on television and for the likes of NT Live and RSC Live from Stratford-upon-Avon.

Olivier opened in Michel St Denis’ production of the Scottish play at the Old Vic on 23 November 1937. Earlier that year he had played Hamlet and Henry V for the company as well as Sir Toby Belch in Twelfth Night, and he was still to take on the role of Iago to Ralph Richardson’s Othello. Macbeth had settings and costumes by the design team known as Motley and incidental music for the production was composed by Darius Milhaud. It was clearly a significant event in the theatre season, not least because the Queen attended a matinee performance on 29 November.

Theatrical lore has it that the curse of the play nearly struck when a heavy weight dropped from the flies and almost killed Olivier. Sadly, the indefatigible founder of the Old Vic, Lilian Baylis, died two days after the opening night. Nonetheless, The Times celebrated the staging as ‘lucid’ while recognising that its ‘outstanding merit’ was Olivier’s performance, of which the critic wrote:

Sometimes still he misses the full music of Shakesperian [sic] verse, but his speaking has gained in rhythm and strength, and his attack upon the part itself, his nervous intensity, his dignity of movement and swiftness of thought, above all his tracing of the process of deterioration in a man not naturally evil give to his performance a rare consistency and power. (Anon., ‘Old Vic’, The Times, 27 November, p. 10)

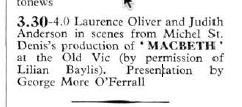

Two weeks after the opening, on Friday 10 December (although Radio Times announced the broadcast for the previous week), members of the company made the journey up the hill to Alexandra Palace to play scenes from their staging in one of the two BBC television studios. It is clear from the television review in The Times that the broadcast included at least one of the scenes with the witches, Lady Macbeth reading her husband’s letter in Act I Scene 5, the exchange with his wife before Macbeth goes off to murder Duncan, and the appearance of Banquo’s ghost at the banquet.

The reviewer was astute in pointing out the advantages that television had over the staging in the theatre:

The weird sisters […] were able to use the resources of the television camera in order to vanish in a most convincing way. Banquo’s ghost, too, was more effective than in the stage production, for, instead of a masked effigy, the real Banquo was there, and then he faded away, leaving Macbeth staring at the spot where he had been. (Anon., ‘Broadcasting: Televised Drama’, The Times, 13 December 1937, p. 18)

At the same time the article acknowledged how the technical limitations of the television image at a point when regular broadcasts had been established only just over a year previously:

Few of the characters [around the table] were shown on the screen at the same time, and there was no complete picture of the banquet.

The intimate nature of early television ensured that it was the duologue exchanges between the murderous couple that were most successful. But the key problem for the reviewer of this stage-to-screen translation was one which remains a concern in all discussions of multi-camera presentations of staged plays:

Mr Laurence Olivier and Miss Judith Anderson [as Lady Macbeth] were also extremely effective, though they made no attempt to moderate their voices to television scale, and still spoke to the utmost recesses of an imaginary theatre, whereas their smallest whispers would have been heard by the unseen audience. The conventions of the theatre must be got rid of if television is to stand on its own [emphasis added].

Here then, right at the start of the medium, is the prescription – which arguably continues to be widely believed today – that television ‘to stand on its own’ must be liberated from its theatrical influences.

The reviewer continues the intermedial comparison by praising the ‘cinematic’ qualities of another recent television broadcast, also of a stage play although not of a specific theatre presentation. Eric Crozier had mounted on the afternoon of 6 December a studio production of Moss Hart and George Kaufman’s comedy about Hollywood, Once in a Lifetime.

The technique of the cinema […] was freely drawn on for Once in a Lifetime, which was excellent entertainment from the first moment to the last, and the ingenuity by which the scenes were made to succeed one another without loss of time was remarkable. If television can be as good as this, it will be real rival to the films [emphasis added].

Crozier’s production was to be one of the most popular of early television dramas and it would be presented on five further occasions in 1938 and 1939. For the reviewer for The Times, it was clear that television’s future lay in aspiring to the cinema and leaving behind the theatre, a path that it can be argued the medium has followed across the seventy-six years since the review was written.

Images: the two main photographs are featured here using Getty Images’ new embedding tool which permits non-commercial use of images provided that an acknowledgement and link to Getty Images is included. The first image shows the banquet scene from the 1937 Old Vic production of Macbeth on stage, while the second is of Judith Anderson and Laurence Olivier as Lady Macbeth and Macbeth.

Interesting to read that vanishing effects were employed, apparently effectively, this early in television history given the primitiveness of the technology. How would that have been achieved ‘live’? I can only guess a piece of set was duplicated in the studio so that a fade between identical camera shots on each set, on one of which is a performer, would make it appear that the actor was appearing or disappearing from the one set. Any other ideas?

Posted by Oliver Wake | 30 March 2014, 8:40 pmThanks Oliver. I have seen a mention in other contexts of a similar effect which was achieved by superimposing two camera shots (which was possible with the crude mixing desk) – one showing the main scene and one showing the characters who were to “disappear”. Then a simple fade-out of the latter achieved the necessary disappearance. In general I think that the early television language of the studio was more sophisticated than we now imagine.

Posted by John Wyver | 31 March 2014, 10:05 amThanks John. I hadn’t realised superimposition was available at that time. I’m pleased to see that, as more research and writing on early television is done, the dismissive old idea of early TV drama being ‘photographed theatre’ becomes increasingly questionable.

Posted by Oliver Wake | 31 March 2014, 4:45 pm