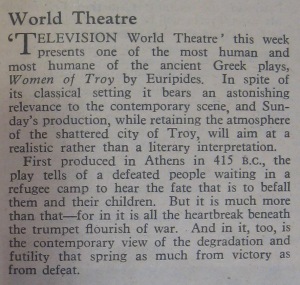

In August this year I blogged about the first well documented (and possibly first ever) production of Greek tragedy to appear on British television—the 1958 BBC Women of Troy, the harrowing tragedy by Euripides that follows the fates of the women after Troy has been sacked and their husbands killed—which was produced by Casper Wrede and Michael Elliott and broadcast as part of the Television World Theatre series. In that post I noted how the production had, in reviews, suffered by comparison with earlier stage and radio productions of the play which were famed for Gilbert Murray’s poetic translation and Sybil Thorndike’s performance as the defeated Trojan queen Hecuba, and also how it had received a mixed reception from the approximate five million viewers which ranged from ‘discomfort and distaste’ to being greatly impressed and moved (BBC WAC VR/58/32).

An eighteen-minute excerpt, from approximately half an hour into the production, was recorded for the BBC archive. Thankfully, the BBC still have a copy of it which is accessible via the research viewing service at the BFI National Library. Today I write about my impressions of this excerpt, which are also informed by having acquired a copy of the camera script from the BBC Written Archives Centre.

What is immediately interesting from reading the script is that the production dispensed with the divine prologue in which Athena asks Poseidon for his help in securing a miserable journey home for the Greeks who, when conquering Troy, violated her temples. Instead it opens directly with Hecuba whose opening speech (‘Up, look up, rise from the earth! There is no Troy any more, I am not queen here, my good days are gone—I must learn to bear the change royally’, in Wrede and Elliott’s television adaptation of Kenneth Cavander’s translation) follows immediately on from extracts of films showing crowds of refugees, burning cities, and even the explosion of an atom bomb―perhaps suggestive of the perceived threat, or fear, of nuclear war at this time―and a series of captions (for example, ‘Knowledge of the trials and struggles of the past is necessary to all who would comprehend the perils that confront us today’) which are paraphrases from the Preface to Winston Churchill’s recently published A History of the English-Speaking Peoples (1956-58). These captions were followed by a final one setting the time and place; here, the assertion that Troy was sacked in 1154 BC (when, in fact, the date of the Trojan War is far from certain) no doubt lent the opening of the play a more vivid sense of historical accuracy, whilst the absence of the gods and the use of introductory film clips and Churchillian quotations seek to establish some kind of connection between the devastation of ancient Troy and the potential for destruction in the modern world.

The recorded extract starts with the beginning of the second choral ode and the scene that follows in which Andromache, wife of the Trojan hero Hector, learns from the Greek herald Talthybius that the Greeks are going to kill her son Astyanax (this takes up almost 300 lines of the Greek text, or about a fifth of the play). So far in the play, the former Trojan queen Hecuba has mourned her fate, Talthybius has announced that the Trojan women have been allocated to the Greeks as spoils of war and the prophetess Cassandra, Hecuba’s daughter, played by Dilys Hamlett (1928-2002), has foretold some of the disasters that will befall the conquering Greeks.

After Cassandra is led off to join Agamemnon, Hecuba collapses and looks back on her former royal life and humble future as Odysseus’ slave-woman. It is at this point that the recorded extract begins. The camera picks out small groupings of women, young and older, who sit amongst rubble, tending to small fires, cooking, talking and nursing each other.

The camera work and the set design (by Norman James, who would go on to co-direct and design the science fiction drama series A for Andromeda in 1961) combine to bring intimacy to the scene: the women are arranged in groups across a variety of levels amidst piles of rubble and around small fires on which they cook. The women face different directions in a natural arrangement and the camera fluidly moves from one group to another. Casper Wrede and Michael Elliott’s desire to achieve the ‘topographical realism’ of the ‘undulations in the earth’ via extensive use of rostra was well achieved by James (memo from Elliott to H.D.Tel, 8 November 1958, BBC WAC T5/2438/1).

These ordinary women of Troy are members of the chorus who deliver a few lines each of Cavendar’s conversational translation-adaptation of the Greek choral ode which narrates how the Greeks entered Troy via a massive wooden horse which the Trojans (mis-)understood to be an offering to the gods on departing home for Greece. As the women begin to recollect, through short phrases and sentences, the arrival of the wooden horse outside the doors of Troy, the camera follows the path of one women who brings water, carried in a shell, to the mouth of a prostrate older women who is clearly suffering (see adjacent image). Another woman, lying down and struggling with a difficult cough, recalls how they interpreted the horse as a sign that the war with the Greeks was over. The camera pans left to others who recall the craftsmanship of the wooden structure, its sheer size, and how the Trojans dragged it through the streets until they had brought it as an offering at the temple of Athene.

The camera moves to another group of four women who are sat close around a fire, eating, and recalling the absolute joy of that night:

JUNE: It was dark enough, too, that night, without a moon.

ANITA: I got into the procession in our street, just behind the man playing the flute so they couldn’t hear I was singing out of tune …

IDA: I sang too, all the old songs I hadn’t sung since before the war. The children had never heard them, made me feel old …

JUNE: I wanted to dance that night, so I went up to the square … the crowd there lifted me off my feet.

ANITA: We were packed so tight I nearly burnt the hair off some old men with a torch I was carrying. But they laughed, they were happy too … Where did you go?

FANNY: I found my own way about … I enjoyed it …

IDA: I had a game as well―for the children―counting the beacons on the hill. I wish I could have taken them up to see …

JUNE: But the biggest fire was the one we danced round in the square. I never knew who he was but we danced all night.

ANITA: No one slept, we made sure of that …

This colloquial, modern translation of the Greek (which, in James Morwood’s close translation published by OUP in 2000, reads ‘Which of the young women, which old man did not come from their houses? Delighting in their songs, they embraced the trick that was their ruin. […] And when the darkness of night fell upon our joyous toil, the Libyan pipe and the Phrygian songs rang out, and the maidens raised and tapped their feet as they sang a happy song’) is full of humanity and it cannot fail to bring to mind the joyous celebrations of VE Day just thirteen years earlier and therefore well within living memory. The chorus members here, young women identified in the script by their real-life forenames (including June Brown, second from the right in the image above, now most widely known as Dot Cotton in Eastenders), softly giggle and laugh as they recall that day, only for the mood to shift again as others recall how the jubilation turned to alarm when the Greeks emerged from their hiding place within the wooden horse:

ROSALIND: The children woke and the little one began to cry. They came to my bed to touch me, and make sure I was there. They were cold and half asleep. I could feel their little hands trembling.

The chorus women then spot that the Greeks are leading Andromache and her son Astyanax back and carrying her dead husband Hector’s armour. (Astyanax, played here by David Franks who was around eight years old, is usually portrayed as a baby on stage, the lifeless body of whom is, later in the play, perhaps more easily represented.)

With the end of the choral ode and the move to the next scene with the royal Hecuba (played by Catherine Lacey, 1904-1979) and Andromache (Rosalie Crutchley, 1920-1997) in conversation, the register of the dialogue shifts from easy and natural to much more reserved, a shift which is perhaps intended to reflect their royal status. There is emotion — Hecuba sheds a tear when Andromache tells her that her daughter Polyxena is dead, for example — but none of the more open sobbing that we witnessed amongst the chorus women. Andromache gives her big speech, in which she talks first of the good fortune of those like Polyxena who, having died, don’t have to live through the current and future misery and then of her devotion to Hector and the difficulties that lie ahead when she will become the property of his killer, the Greek hero Achilles. The camera naturally focuses on her when she is talking, but what I liked was how it also captured in the distance the other Trojan women who were otherwise engaged—just sitting, head in hands, or facing away, lost in their own thoughts and occupations. Often the choruses in productions of Greek tragedy attend to the words and movements of the lead characters closely, but here the viewer is given more of a sense of the anguish of all of these women, which of course builds on the intimacy and domesticity of the previous scene in which they spoke movingly of their own memories and experiences.

Talthybius, played by Colin Keith-Johnston (1896-1980), enters to announce that Astyanax will not be following his mother to Greece but is, in fact, going to meet his death in Troy. Andromache clutches Hecuba in grief (see adjacent image) and then runs to her boy and embraces and addresses him on her knees (see the shot at the top of the page). She gives an impassioned speech before they are led off separately.

Hecuba then utters a brief speech which concludes, ‘I command nothing but tears … My city, my son! What more can come. The last grain of life is crushed from me, and I become one of the living dead’, whereupon she curls up on the floor and the camera swoops effectively up so that when we look down on her she may indeed be mistaken for a corpse.

And thus ends the brief audiovisual record of the BBC’s 1958 Women of Troy.

O how I would have liked to see how Dilys Hamlett played the crazed Cassandra, or how the Helen and Menelaus scene—played by Diana Churchill (1913-1994) and Patrick Wymark (1926-1970)—was done (though we do have the adjacent still from a review), but I’m thankful that this short excerpt, at least, has been preserved as it has enabled me to appreciate the production at a closer distance and with more care than one can possibly do secondhand through reviews and internal memos.

The question as to why this extract was filmed, however, still puzzles me. I wonder whether our readers can offer any ideas about why only an eighteen-minute excerpt would have been telerecorded ‘for archives’, as an internal memo notes (C. Logan to P.M.Tel., 10 January 1958, BBC WAC T5/2438/1)?

But what is now clear, thanks to my colleague John Wyver, is that the brief break which takes place roughly in the middle of the recording (with no break in the action—rather momentary overlap) comes about from a switch from one film camera to another: the BBC memo notes that the telerecording is to be made on 35mm film, and John informs me that each reel of film would have lasted for ten minutes.

It’s not uncommon for versions of Trojan Women to drop the Athena/Poseidon prologue. Michael Caccoyannis’ movie version does this, as did Katie Mitchell’s recent National Theatre production. I don’t know how common this approach was in 1958.

What does the internal memo actually say? If the film recordings were done in approximately ten-minute chunks, then this eighteen minutes would appear to be two of those chunks. But are they the only chunks recorded, or are they instead the only two to survive? were they picked out to be preserved, or has this come about by accident?

Posted by tonykeen46 | 1 December 2011, 11:18 amThanks for your thoughts, Tony. The internal BBC memo is pretty clear on this point: ‘it has been decided to make a 35mm telerecording for archives of the above play. Only a 15 minute excerpt will be recorded for archives […] All costs for the 15′ recording should be charged to code 197’. Now, perhaps, to find out what code 197 stands for!

Posted by Amanda Wrigley | 1 December 2011, 11:30 amI fear I don’t know what charge code 197 is (although we must try to discover that) but I find it really interesting that the BBC should record only 15 minutes of a production ‘for archives’. I don’t know of another such example, where only a part of a drama was tele-recorded, and I’m intrigued to know if there are any other documented part-recordings. I suppose it was driven by a concern to keep costs for a minimum, since 35mm stock and processing would not have been cheap.

Posted by John Wyver | 1 December 2011, 1:32 pmI have an idea in my head that there is some evidence that short scenes from dramas, either single plays or series, thought to be particularly significant, were recorded for archive purposes – but I can’t establish that for certain, and if John’s never heard of such I may just be misremembering. I think the approach was common in factual and documentary programming.

The memo does perhaps cast an interesting light on the BBC’s attitudes to the programme. On one level, they considered it important enough to preserve fifteen minutes – which may suggest that it was indeed the first Greek play the BBC had done. On the other hand, though videotape had yet to arrive, film recordings were routinely made of programmes where there was the potential for a repeat (the cost for the film being considerably less than the cost of remounting a production). So it looks as if the BBC assumed that there was no chance of this play gaining enough of an audience for a repeat.

I presume the rationale behind which scenes to record was one Chorus, and one contiguous Episode – the second chorus and the Andromache episode were perhaps chosen on purely practical grounds, in that they best fitted the fifteen minutes available.

Posted by tonykeen46 | 2 December 2011, 5:11 pmThese are really good further thoughts, Tony. Yes, it’s curious that they thought it important enough to preserve, but only in part! And, as John says, it would be interesting to discover if any other part-recordings exist. I wonder if finding out what charge code is 197 will help us? I’ll certainly post more here if I find out.

Posted by Amanda Wrigley | 5 December 2011, 5:05 pm