Just over twenty years after ITV transmitted a production of Sophocles’ Electra in modern Greek and – astonishingly – without subtitles (about which I wrote a blog post here), the second of the two known reconfigurations of theatre productions of Greek drama for British television was transmitted by Channel 4, less than a year after the network was established. Whereas the modern Greek Electra had posed a linguistic challenge for the audience in 1962, Channel 4’s transmission of Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy in 1983 – a televised version of the National Theatre’s 1981 all-male production directed by Peter Hall – was challenging in terms of its sheer length, for it ran over a 4½-hour slot on the evening of Sunday 9 October.

Just over twenty years after ITV transmitted a production of Sophocles’ Electra in modern Greek and – astonishingly – without subtitles (about which I wrote a blog post here), the second of the two known reconfigurations of theatre productions of Greek drama for British television was transmitted by Channel 4, less than a year after the network was established. Whereas the modern Greek Electra had posed a linguistic challenge for the audience in 1962, Channel 4’s transmission of Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy in 1983 – a televised version of the National Theatre’s 1981 all-male production directed by Peter Hall – was challenging in terms of its sheer length, for it ran over a 4½-hour slot on the evening of Sunday 9 October.

In this long post, I consider the other programmes that accompanied this viewing marathon, before going on to contextualise the production of Agamemnon, the first play in the trilogy, in terms of its place in Channel 4’s cultural programming schedule, think through some of the aesthetic effects of the production’s translation to the small screen and, finally, consider the contemporary critical response to the production.

Culturally educative viewing

The television version of the National’s The Oresteia was prefaced, earlier in the week, by two accompanying programmes. On Tuesday 4 October, a special edition of the Today’s History series, transmitted under the title The Weight of the Past, connected the themes of the Oresteia with ‘modern instances of revenge as a route to justice’, asking ‘how a society ever emerges from feuds to the rule of law’ (Channel Four Television: Press Information, 1-7 October 1983). This programme was illustrated by extracts not only from the Channel 4 production but also from the 1977 Sicilian film Padre, Padrone (directed by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani), which had recently been shown on Channel 4, and the recently released Handgun (written and directed by Tony Garnett, 1982).

On Saturday 8 October, the day before the trilogy was transmitted, the one-hour documentary The Oresteia at Epidaurus featured the company’s tour to Greece in the previous year when they had received the honour of performing the first ever non-Greek-language production of a Greek play in the open-air ancient theatre of Epidaurus. But Andrew Snell’s documentary also deftly weaves together an enjoyable and accessible introduction to the issues of the trilogy, ancient performance conventions and modern production choices through interviews with Peter Hall, Tony Harrison, Harrison Birtwistle, Jocelyn Herbert, the classical scholar Oliver Taplin and several of the actors, including Greg Hicks and Tony Robinson (who was, around this time, becoming well known as Baldrick in the British historical sitcom Blackadder).

On Saturday 8 October, the day before the trilogy was transmitted, the one-hour documentary The Oresteia at Epidaurus featured the company’s tour to Greece in the previous year when they had received the honour of performing the first ever non-Greek-language production of a Greek play in the open-air ancient theatre of Epidaurus. But Andrew Snell’s documentary also deftly weaves together an enjoyable and accessible introduction to the issues of the trilogy, ancient performance conventions and modern production choices through interviews with Peter Hall, Tony Harrison, Harrison Birtwistle, Jocelyn Herbert, the classical scholar Oliver Taplin and several of the actors, including Greg Hicks and Tony Robinson (who was, around this time, becoming well known as Baldrick in the British historical sitcom Blackadder).

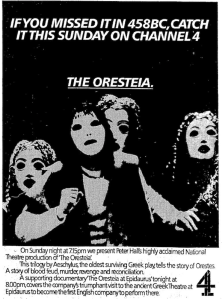

Much of the commentary in part one of the documentary focuses on the use of masks, with Peter Hall offering his interpretation of their power and facility, Jocelyn Herbert commenting on their use on the stage and the actors talking about how they began to find ways of working with the masks in rehearsals. The second half of the programme is more concerned with the new, muscular and rhythmical translation by Tony Harrison who, giving an interview sitting beneath a tree on the ancient site of Mycenae, talks about the nature of the play; this is endorsed and taken further by commentary by the scholar Oliver Taplin. We see the final rehearsal, watch the theatre slowly fill up on opening night (although it is still daylight), and the performance beginning. Some key moments from the drama are shown and the documentary ends with the rapturous standing ovation from the 15,000-strong audience. In this way the ‘big event’ (see below) of the potentially daunting 4½-hour masked Oresteia is broken down, explained, made accessible. Note also how the advert published in The Times, below, plays on the novelty of such a thing as a Greek play being shown on television: ‘If you missed it in 458 BC, catch it this Sunday on Channel 4’.

Much of the commentary in part one of the documentary focuses on the use of masks, with Peter Hall offering his interpretation of their power and facility, Jocelyn Herbert commenting on their use on the stage and the actors talking about how they began to find ways of working with the masks in rehearsals. The second half of the programme is more concerned with the new, muscular and rhythmical translation by Tony Harrison who, giving an interview sitting beneath a tree on the ancient site of Mycenae, talks about the nature of the play; this is endorsed and taken further by commentary by the scholar Oliver Taplin. We see the final rehearsal, watch the theatre slowly fill up on opening night (although it is still daylight), and the performance beginning. Some key moments from the drama are shown and the documentary ends with the rapturous standing ovation from the 15,000-strong audience. In this way the ‘big event’ (see below) of the potentially daunting 4½-hour masked Oresteia is broken down, explained, made accessible. Note also how the advert published in The Times, below, plays on the novelty of such a thing as a Greek play being shown on television: ‘If you missed it in 458 BC, catch it this Sunday on Channel 4’.

In between the three acts there were two 10-15 minute interludes: the first was ‘a combination of dance and computer graphics; movements choreographed to computer overlay and to the specially composed music of David Cunningham which, in turn, was inspired by the music of the Oresteia’; the second comprised the jazz saxophonist Lol Coxhill’s musical improvisations, which were also inspired by Birtwistle’s score (Channel Four Television: Press Information, 8-14 October 1983).

In between the three acts there were two 10-15 minute interludes: the first was ‘a combination of dance and computer graphics; movements choreographed to computer overlay and to the specially composed music of David Cunningham which, in turn, was inspired by the music of the Oresteia’; the second comprised the jazz saxophonist Lol Coxhill’s musical improvisations, which were also inspired by Birtwistle’s score (Channel Four Television: Press Information, 8-14 October 1983).

This plethora of associated, supportive programming around the Oresteia very much reminds me of a 3¾-hour production of the same trilogy broadcast on BBC Radio’s Third Programme in 1956 which had been accompanied by a substantial series of culturally educative programmes. In addition to a prefatory talk by the translator of the plays, the production was followed in subsequent weeks by lectures on the interpretation of the trilogy in terms of theology and morality by the classicist Hugh Lloyd-Jones and a programme in which Elsa Vergi of the Greek National Theatre read extracts from the trilogy in Greek interspersed with summaries in English. It was not unusual for the BBC, especially on radio, to accompany ‘highbrow’ cultural broadcasts with explanatory programming, and early Channel 4 was clearly, in its own way and in televisual form, doing a very similar thing with its Oresteia.

The young Channel 4

… to provide a distinctive service; to innovate in form and content; to deal with interests and groups not served by commercial television, or perhaps any television; to draw programmes from a wider range of production sources than those which constituted the existing industry. (Michael Kustow, One in Four, p. 10)

In October 1983 Channel 4 was, of course, in its infancy. The new network, launched on 2 November 1982, had chosen to focus its arts resources on actual performance – ‘the big event’ – in deliberate contrast with the long-running arts and culture series Arena and Omnibus on the BBC from 1975 and 1967 respectively and The South Bank Show on ITV from 1978 (Jeremy Isaacs, Storm over 4, pp. 168-69: see below for the full bibliographical references). ‘We attached a high priority to the arts’, recalls Jeremy Isaacs, the founding Chief Executive of the network to 1987: ‘we couldn’t help but be distinctive in doing so, since no one else did’ (Look Me in the Eye, p. 359).

In October 1983 Channel 4 was, of course, in its infancy. The new network, launched on 2 November 1982, had chosen to focus its arts resources on actual performance – ‘the big event’ – in deliberate contrast with the long-running arts and culture series Arena and Omnibus on the BBC from 1975 and 1967 respectively and The South Bank Show on ITV from 1978 (Jeremy Isaacs, Storm over 4, pp. 168-69: see below for the full bibliographical references). ‘We attached a high priority to the arts’, recalls Jeremy Isaacs, the founding Chief Executive of the network to 1987: ‘we couldn’t help but be distinctive in doing so, since no one else did’ (Look Me in the Eye, p. 359).

The channel’s arts output began with a television version of the Royal Shakespeare Company’s theatre production of Nicholas Nickleby, included Bill Bryden’s The Mysteries for the National and Peter Brook’s Mahabharata, and encompassed regular Sunday afternoon opera. Many of these projects were commissioned by Michael Kustow, Channel 4’s Commissioning Editor for the Arts, who had previously worked at the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company. Kustow recalls that he sought ‘not television about the arts, but art television’ (‘Prime-time piffle: 25 years of Channel 4’, The Independent, 5 September 2007). His goals were, on the one hand, to ‘keep alive heightened expression, poetry in speech and classic form’ and, on the other, for these works to be seen by new audiences:

Reaching half a million people, a derisory number in television rating terms but three times the number that saw the Oresteia at the Olivier Theatre, means that some of those viewers are plunged into a classic for the first time. And if there’s a marriage between the visual language and performance style of the theatre work and the codes of television, those viewers may stay tuned. And if you back the thing up with informative documentary and print, as we did with the Oresteia and The Mysteries, you may have opened new interests and appetites people didn’t know they possessed. Because they are cumulative over the years, these things are difficult to measure on television’s ‘appreciation index’. (Michael Kustow, One in Four, pp. 17-18)

It is a production that has been much admired, and almost as strongly disliked and derogated. (Oliver Taplin, ‘The Harrison Version’, p. 235)

In his essay, the classical scholar Oliver Taplin, who was involved in the production (and the documentary: see above), talks about how this theatre production made a rare attempt to reflect the importance of music, rhythm and tone in the play’s ancient performance with its achievement of an energetic dynamic between Tony Harrison’s words and Harrison Birtwistle’s music. He discusses how the stage production excelled in its ‘momentum, pace, dynamic, rhythm — a constant sense of dramatic urgency and forward movement’, focusing on the example of how the production made the non-naturalist Greek dramatic convention of stichomythia (passages of rapid-fire single line dialogue between two speakers), underscored by rhyme and Birtwistle’s score, a particularly potent feature (ibid., p. 235-237).

To what extent did such characteristic aspects of this powerful production successfully translate to the television medium and how did the selective eye of the camera enhance or detract from them?

The performance for television was filmed in the Olivier Theatre; or, rather, three full performances were captured on four cameras, resulting in twelve full-length recordings which Peter Hall took a very long time to edit. The resulting programme was broadcast on Channel 4 and also made available for purchase from an American educational supplier on three (incredibly expensive) VHS tapes, suggesting that they were considered to have an educational utility alongside their landmark theatrical status. A search of www.worldcat.org confirms that many academic libraries in the UK and across North America still hold this title on their shelves, nearly thirty years after it was originally broadcast.

The television version (which, along with the documentary, is accessible in the RNT Archive) opens with the caption ‘The Oresteia Trilogy by Aeschylus’ followed by the names of the translator, designer, composer and director shown in white letters against a slow panning shot, from below, across the seated audience who are waiting for the performance. Viewers who watched the previous evening’s documentary heard that the Olivier had actually been modelled on the ancient theatre at Epidaurus, and so the perspective and subject of this shot is designed to underline the correspondence between Epidaurus and the Olivier, whilst the panning shot, from below, of the seated, chattering audience mirrors a similar shot of the Epidaurus audience shown in the documentary (the significant difference being, of course, that the open-air performance began in the light of early evening, whilst the television version is shot inside a closed performance space, darkly lit).

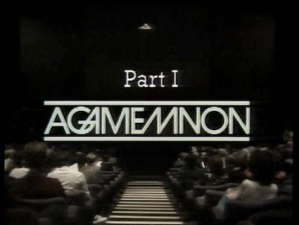

The camera abruptly switches perspective: we are now high up, looking down past the rows of audience either side of the stairs towards the stage which is in total darkness apart from the light on one tiny figure, situated high up — the Watchman (just visible in the adjacent image). The caption ‘Part I. Agamemnon’ appears quickly and fades, the lights dim, and we move to a close-up of the Watchman — a perspective which, of course, would not have been possible for the theatre audience. His opening speech is captivating, funny in places, and given in David Roper’s strong Bradford accent. He appears to be speaking directly to camera, with striking and good use of gesture and head movement, making for an arresting start to the production.

The camera abruptly switches perspective: we are now high up, looking down past the rows of audience either side of the stairs towards the stage which is in total darkness apart from the light on one tiny figure, situated high up — the Watchman (just visible in the adjacent image). The caption ‘Part I. Agamemnon’ appears quickly and fades, the lights dim, and we move to a close-up of the Watchman — a perspective which, of course, would not have been possible for the theatre audience. His opening speech is captivating, funny in places, and given in David Roper’s strong Bradford accent. He appears to be speaking directly to camera, with striking and good use of gesture and head movement, making for an arresting start to the production.

On the Watchman’s exit, Birtwistle’s score accompanies the parodos, the traditional entry of the chorus onto the set. Here we get for the first time a rare glimpse of the full extent of the set, which with its large circular playing space and raised playing space at the back of the stage echoes elements of ancient theatres. The chorus break into their ode, their rhythmically delivered lines punctuated throughout by the percussive elements of the score. The camera shots, too, often take their cue from the line breaks in Harrison’s text, sometimes making for a rapid succession of similar shots which, although they keep pace with the lines and music, are not – for this viewer – sufficiently differentiated to be worthwhile and engaging.

On the Watchman’s exit, Birtwistle’s score accompanies the parodos, the traditional entry of the chorus onto the set. Here we get for the first time a rare glimpse of the full extent of the set, which with its large circular playing space and raised playing space at the back of the stage echoes elements of ancient theatres. The chorus break into their ode, their rhythmically delivered lines punctuated throughout by the percussive elements of the score. The camera shots, too, often take their cue from the line breaks in Harrison’s text, sometimes making for a rapid succession of similar shots which, although they keep pace with the lines and music, are not – for this viewer – sufficiently differentiated to be worthwhile and engaging.

Close-ups of the members of the Chorus sometimes show glimpses of lips moving through the mask’s mouthpiece and torsos inflating with the breath required to keep up with the energetic script which is chanted and sung at points. Despite these small signs of life beneath the near-identical masks and extremely similar costumes (in shades of grey and brown), the continuing focus on the gently moving figures and immobile mask-faces lends a very static character to this opening choral ode. Some shots of the audience or the whole stage would have helped to open things up a bit; a little more movement would have helped even more. It is also apparent that the use of such a rapid sequence of shots, selected from the films of the four variously located cameras, also lends a sense of slight dislocation, as the chorus seem to look in a number of different directions from line to line.

Enter Clytemnestra, and the chorus scatter as the palace doors open and she walks forward. The actor Philip Donaghy’s evidently male body and voice in a feminine dress, walk and stance effectively captures the way in which Aeschylus portrays Clytemnestra as a women with some masculine qualities. (This is rendered by Harrison in the translation as ‘That woman’s a man the way she gets moving’ and ‘You feel like a woman but talk like a man talks’.)

Enter Clytemnestra, and the chorus scatter as the palace doors open and she walks forward. The actor Philip Donaghy’s evidently male body and voice in a feminine dress, walk and stance effectively captures the way in which Aeschylus portrays Clytemnestra as a women with some masculine qualities. (This is rendered by Harrison in the translation as ‘That woman’s a man the way she gets moving’ and ‘You feel like a woman but talk like a man talks’.)

Shortly, things liven up even more with the swift entrance of Agamemnon on his chariot, followed by Cassandra in a cage. When they swing round the circular playing space the camera moves back and we see the shape of the stage and the lights above, and these indisputable signs that we are in a theatre strangely inject some welcome energy into the production.

The scene between Clytemnestra and Agamemnon, in which she cleverly persuades him, despite his gut instinct otherwise, to walk into the palace on a fine purple cloth which is good enough to honour the gods with (and which, as such, a man should refrain from treading on) is powerfully played. As the two actors engage in the passage of stichomythia at the climax of their discussion, the camera and score work beautifully together to punctuate the shifts from one shot to another. As Agamemnon moves slowly towards the doors of the palace – where he will meet his death at his wife’s hands – the camera moves back and forth between close-ups of his bare feet on the cloth, the watching Chorus, and Clytemnestra. The effect is reminiscent of the eyes of a fully engaged audience member darting back and forth between the different performance elements on stage – but in a more formal and stylised way, choreographed by the regularity of Birtwistle’s percussive music.

The scene between Clytemnestra and Agamemnon, in which she cleverly persuades him, despite his gut instinct otherwise, to walk into the palace on a fine purple cloth which is good enough to honour the gods with (and which, as such, a man should refrain from treading on) is powerfully played. As the two actors engage in the passage of stichomythia at the climax of their discussion, the camera and score work beautifully together to punctuate the shifts from one shot to another. As Agamemnon moves slowly towards the doors of the palace – where he will meet his death at his wife’s hands – the camera moves back and forth between close-ups of his bare feet on the cloth, the watching Chorus, and Clytemnestra. The effect is reminiscent of the eyes of a fully engaged audience member darting back and forth between the different performance elements on stage – but in a more formal and stylised way, choreographed by the regularity of Birtwistle’s percussive music.

At several other points do the cameras’ various close-ups of the immobile mask, the text of the play and the score work in real harmony. When Agamemnon and Cassandra are in the palace being murdered, the camera moves from mask to mask amongst the Chorus. As they utter the following lines, their immobility and the lack of accompanying gesture or movement underscores the fixed nature of the Chorus in the orchestra, the circular playing space (because Greek tragic convention dictates that they do not enter the stage building, and indeed they rarely take any actual action), and at this point it works particularly well to emphasize their sense of fear and impotence in the face of the murders Clytemnestra is enacting within the palace.

At several other points do the cameras’ various close-ups of the immobile mask, the text of the play and the score work in real harmony. When Agamemnon and Cassandra are in the palace being murdered, the camera moves from mask to mask amongst the Chorus. As they utter the following lines, their immobility and the lack of accompanying gesture or movement underscores the fixed nature of the Chorus in the orchestra, the circular playing space (because Greek tragic convention dictates that they do not enter the stage building, and indeed they rarely take any actual action), and at this point it works particularly well to emphasize their sense of fear and impotence in the face of the murders Clytemnestra is enacting within the palace.

I fear that those screams mean that our clanchief’s slain

Now we should take counsel

And every man should say what he thinks is the safest plan.

In my opinion we ought to bring

The whole city here to help the king.

And I say rush in, break down the door

Catch them with swords still dripping with gore.

In addition to the Chorus’ static poses and immobile heads here, a pause of a couple of seconds follows on from the line ‘And every man should say what he thinks is the safest plan’: in other words, no-one knows or wants to say what ought to happen next. They are utterly frozen.

The outcome of those murders – the corpses of Agamemnon and Cassandra – are, again, according to ancient convention, wheeled out through the palace doors on a low platform (the ekkyklema in Greek) for the Chorus, and the audience, to see. The camera here enables us to look upon the corpses, entangled in a net like fish, more closely than the theatregoer, as it had with Agamemnon’s feet treading on the red tapestry on his way into the palace. This makes for a fabulous tableau, with Agamemnon’s left forearm erect, and the lifeless Cassandra lying between his legs (see adjacent image). There are definitely sexual elements to this scene, particularly Clytemnestra’s ecstatic rendition of the lines:

The outcome of those murders – the corpses of Agamemnon and Cassandra – are, again, according to ancient convention, wheeled out through the palace doors on a low platform (the ekkyklema in Greek) for the Chorus, and the audience, to see. The camera here enables us to look upon the corpses, entangled in a net like fish, more closely than the theatregoer, as it had with Agamemnon’s feet treading on the red tapestry on his way into the palace. This makes for a fabulous tableau, with Agamemnon’s left forearm erect, and the lifeless Cassandra lying between his legs (see adjacent image). There are definitely sexual elements to this scene, particularly Clytemnestra’s ecstatic rendition of the lines:

He lay there gasping and splurting his blood out

Spraying me with dark blood-dew, dew I delight in

As much as the graincrop in the fresh gloss of rainfall

When the wheatbud’s in labour and swells into birthpang.

She gets angry, condemning her husband as ‘Shagamemnon, shameless, shaft-happy, ogler and grinder of Troy’s golden girlhood’, ramming home the sense of betrayal she feels at his bringing home as concubine Cassandra, on top of the greater loss of their daughter Iphigenia, whom he sacrificed to gets favourable winds for the sea journey from Greece to Troy. In this scene, the fixed camera shot, with occasional close-ups, works well. There is nowhere else one would wish to look in this scene.

She gets angry, condemning her husband as ‘Shagamemnon, shameless, shaft-happy, ogler and grinder of Troy’s golden girlhood’, ramming home the sense of betrayal she feels at his bringing home as concubine Cassandra, on top of the greater loss of their daughter Iphigenia, whom he sacrificed to gets favourable winds for the sea journey from Greece to Troy. In this scene, the fixed camera shot, with occasional close-ups, works well. There is nowhere else one would wish to look in this scene.

Critical reception

Critical opinion of the television production was polarised. John Naughton, writing in The Listener, considered that ‘although one could guess at the theatrical impact of the stage production, it didn’t work on the box. It was like looking at great events through a keyhole, or the wrong end of a telescope: interesting, but distant’. Lynne Truss of The Times Educational Supplement was similarly disappointed: ‘it is a pity that, as the production was filmed during public performances, there is not more sense of it as a theatrical event. There are few shots of the whole stage (so the groupings of the chorus are sometimes missed), there are no shots of the musicians, and, saddest of all, there is no applause at the end. In the Epidaurus programme, the enthusiastic reception is thrilling’. Robin Buss, also of the TES, had a more general criticism: ‘if C4 wants to commit hara-kiri, this is a safe, even a noble way to do it. Culture is not popular, but it is non-controversial and everyone knows that is a good thing. C4 appears to have decided that, if it has to go, its suicide note will take the form of a pious condemnation of our philistine disregard for Greek drama’.

Those who were left deeply impressed by the production often had praise for the technical aspects of the production. Note how some of the same points arose for those who liked it and those who did not so much. Michael Wood, writing in New Society, considered that:

rather than simply being recorded for/by television it has been genuinely translated, given a new and different life by fluent photography and fast, imaginative editing. We rarely see the whole stage, for example. The camera moves from face to face (from mask to mask), waiting only the length of a line or a cadence, picking up groupings of the chorus, now one, now two, now five heads, framing two protagonists as they quarrel, cutting to silent characters for their gestures of reaction, putting Agamemnon’s foot in a giant close-up as he steps on the purple cloth which will lead him to his murder. Apparently four cameras were set up in different spots for three full performances, leaving Hall with 48 hours of film to edit. The result is not only that television sees the plays for us, chooses emphases not available to a theatre audience, but that something like a musical dimension is added. […] Everything in Hall’s production – words used, rhythms of speech, stylised gestures, unmoving masks, pauses, silences – helps us to see not what these characters feel but what their tactical and formal position is: the father-murdering mother faces the mother-slaying son.

The freedom that Peter Hall gave the cameraman impressed some critics including Alix Coleman in the TV Times – who reports Hall as saying, ‘There was no shooting script. I’d say, shoot what interests you. You’re free. They were fascinated and had a great deal of fun” ’ – and Julian Barnes in The Observer. Barnes goes on to write that ‘The masks (no longer dampening the actors’ delivery, as in the theatre) were a great success: the camera prowled from one to another, shifting the angle of vision, cutting away suddenly, and giving these formal disguises an immediacy and flexibility beyond that available to the static viewer in the stalls’.

Suzie Mackenzie’s write-up in Time Out, 6 October 1983, offers perhaps the most balanced assessment of all:

this epic rendering […] adds as much as it loses to the original experience. It is still Harrison’s verse that carries you through and the masks still possess that eerie quality of actually transmitting emotions to the audience. But most obviously the sweeping mise en scene of Peter Hall’s original production is replaced by an attention to nuance that is impossible without the focus of a camera and editing. Prepare yourself for a marathon and submit to the natural pull of television. This is one occasion when the concentrated intimacy of the box is a real plus.

Bibliographical references

Julian Barnes, ‘Delving into Dr Newman’s Casebook’, The Observer, 16 October 1983.

Robin Buss, ‘The Gadfly Grows Wary’, The Times Educational Supplement, 4 November 1983, p. 20.

Alix Coleman, ‘Happy Tale of a Greek Tragedy’, TV Times, 8 October 1983, pp. 76-78.

Peter Hall, Exposed by the Mask: Form and Language in Drama. London: Oberon, 2003.

Jeremy Isaacs, Storm over 4: A Personal Account. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1989.

— Look Me in the Eye: A Life on Television. London: Abacus, 2006.

Michael Kustow, One in Four: A Year in the Life of a Channel Four Commissioning Editor. London: Chatto & Windus, 1987.

— ‘Prime-time piffle: 25 years of Channel 4’, The Independent, 5 September 2007.

John Naughton, ‘Television: Crescendos in the Living-Room’, The Listener, 13 October 1983.

Oliver Taplin, ‘The Harrison Version: “So long ago that it’s become a song?” ’, in Fiona Macintosh, Pantelis Michelakis, Edith Hall and Oliver Taplin (eds.), Agamemnon in Performance, 458 BC to AD 2004, pp. 235-251. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lynne Truss, ‘Masked Celebration’, Times Educational Supplement, 7 October 1983.

Michael Wood, ‘Family at War’, New Society, 6 October 1983, p. 19.

Acknowledgements

Warm thanks to Gavin Clarke of the RNT Archive, Justin Smith and Ieuan Franklin of the Channel 4 and British Film Culture research project at the University of Portsmouth, and Graham Nelson of St Anne’s College, Oxford for generous help with research materials.

Thank you for your article, which I read with delight.

I’ve been trying to source a copy of this production commercially for some time, for home viewing. Unfortunately, it seems it is only viewable at the RNT Archive and a few restricted-access libraries internationally, mainly as ancient VHS copies. Other than the odd second hand VHS tape on Amazon, there is now no way to obtain a copy of the Oresteia from Channel 4, the Royal National Theatre, Films for the Humanities, or any other distributor.

Fair enough, one can understand the commercial realities of making this production available.

However what I find particularly irksome is that, having decided to cease offering this production via commercial means, Channel 4 then also asserts its copyright to ban its access on YouTube.

The interested viewer is now simply unable to see the plays. Perhaps Channel 4 did not consider that this effectively kills the RNT production as living culture. It undermines the cultural heritage of Channel 4, which this article celebrates. For most of us, the RNT production now only exists as art criticism.

I’d much rather be able to watch the plays rather than read art criticism, however interesting.

When will Channel 4 make this heritage production available again, whether through the public domain or modern commercial media?

Posted by Charles | 4 February 2012, 12:55 amThank you, Charles, for raising this really important issue. I don’t know whether it will ever be released commercially again, or what the hurdles to doing so would be, but what I can say is that the trilogy will, almost definitely, be shown through a Saturday at the BFI Southbank in June 2012. Screen Plays is working with the BFI on showing a season of some of the Greek plays I’ve been writing about on the blog, and we’ve recently had it confirmed that there is space in the schedule for the full trilogy, which is fantastic. As soon as dates are confirmed we will, of course, make the information available on the blog, and we do hope that this will enable people such as yourself to see these rather rare recordings.

Posted by Amanda Wrigley | 5 February 2012, 8:41 pmThank you for all the information on both this and the Serpent Son, which I think is the one I personally vaguely remember… I’m working on comparing the BBC Iphigenia at Aulis with Cacoyannis’ version at the moment, and I can see this site is going to be of great help to me!

Two comments:

1) Re Charles’s query: is this maybe a case of there being too many interested parties who all have to agree? Not just Channel Four but also the National Theatre, and possibly Hall/Harrison/Birtwhistle/… as well? The trouble appears to be sometimes that getting everyone involved together to agree a policy is just too much bother. Alas for us.

2) I think this may the first time iMDb has let me down – I cannot find any acknowledgement of this television screening at all on their site. Knowing that weird things can happen to titles, I’ve looked up Peter Hall, Tony Harrison, Harrison Birtwhistle, Jocelyn Herbert – but nothing! Is there a potential reason for this, or is it just that I have had too much faith in iMDb in the past – that they are just not so reliable on the obscurer corners of less-then-recent television, in which category I suppose televsised stage productions might be supposed to fall?

Looking forward to seeing you in Nottingham soon, Amanda!

Posted by Lynn Fotheringham (University of Nottingham) | 5 February 2012, 12:51 pmThanks very much for your thoughts on Charles’ point, Lynn, and I’m truly delighted to hear that you are working on the BBC Iphigenia in Aulis. I am now moving on to writing up my thoughts on the Don Taylor productions and there is a possibility that I’ll post something on IA before we meet in Nottingham! It will be really great to talk with you about that because — going back to Charles’ point — so few people have actually seen these productions. You may be interested to know that the IA will conclude the season of Greek plays at BFI Southbank we’re organising this summer!

Posted by Amanda Wrigley | 5 February 2012, 8:46 pmLoved the Oresteia at The BFI last night. Great work Amanda on sorting this for public presentation. It was my introduction to Tony Harrison’s translation. I particularly liked his rendering of Cassandra’s dialogue: sparse, terse and sudden. Her costume was also a treat, as were the wonderfully appropriate clashing sounds. (Not such a fan of misogynistic ending of the trilogy – but we’ll have to forgive aeschylus – he could write a bit!!)

Posted by Ed Sayeed | 24 June 2012, 9:25 amThanks, Ed! I’m reposting on the comments page for last night’s screening so it’s part of the discussion there, too :-)

Posted by Amanda Wrigley | 24 June 2012, 9:36 amI also found Cassandra’s part quite interesting. However I don’t think it conveyed her pathos and sufference. I would have liked her screaming a bit more. :)

Reading Collard notes on Agamennon’s stagecraft I found out that Cassandra is already in prophetic seizure when the Chorus say that she is acting like a wild animal. Whereas in this production she is completely still at that time.

From the same book I also found out that Clytemnestra should be blood-spattered, I found the red glove a bit too minimalistic.

Posted by Suturn | 20 December 2013, 7:33 amStreams are available here:

http://ccccd.ativ.alexanderstreet.com/video/browse/search/Oresteia

rtmpdump can help bring them locally (if needed)

Posted by sebus | 6 November 2012, 2:16 pmBrilliant, thanks for that. I hope that the relevant parties don’t again shut down access to this Oresteia, whether commercial or in the public domain.

Posted by Charles | 7 November 2012, 1:04 amI’m transcribing this now so it should be out with closed captioning in short time. Shhhh

Posted by anonymous | 14 November 2012, 5:58 amThanks very much Amanda for writing the review, and also for all the other comments. It is certainly one of the most powerful plays I have ever seen. I share the frustration about the lack of availability, and see that the Theatre in Video link provided above is not working either – its a US subscription channel so far as I can see. I suspect that it may not so much be getting NT Channel 4 etc to agree but that the rights were rather unfortunately sold on to the current distributors without thinking too much at the time. Its now all rather silly when you can buy recent blockbuster films, series, blue-ray Gyndebourne opera for a max of 30 quid and usually far less. So what to do? I wonder if Tony Harrison and Peter Hall are aware of the situation? A short joint letter from them to Channel 4 and the NT expressing their regret at the situation might do wonders or at least start the ball rolling and perhaps Tony Robinson might also lend a hand. But sadly none of us are getting any younger so if someone has the contacts or at one step removed they need to get their skates on . . .

Posted by Malcolm MacGarvin | 20 November 2012, 9:04 pmThanks for your generous words about the blog piece, Malcolm, and of course you’re right that it would be a great thing if this trilogy could somehow make it onto DVD — and I’m convinced there is a good market for it — but, as you sense, it’s probably not at all a straightforward matter. Certainly, if it should happen, readers of the Screen Plays blog will be the first to hear the news!

Posted by Amanda Wrigley | 21 November 2012, 12:09 amThis is a fascinating blog, Amanda. The complete trilogy is currently available on Youtube although the quality of the screen image is variable (particularly in Eumenides).

Richard

Posted by Richard Potter | 6 April 2013, 4:56 pmReblogged this on E-Learning and commented:

Really interesting blog post here about the Greek plays.

Posted by Louise Taylor | 6 June 2013, 4:20 pmWith there being new productions of Oresteia in London at the moment, I came across the RNT version but only the poor quality youtube ones. I would love to see the whole thing. I have read the comments about the rights being sold on… this is a shame. There is a lot that can be downloaded on iTunes about the RNT production itself but it doesn’t look possible to download the play. I note that BFI did a screening in 2012 – I wonder whether they plan on doing another one soon. Please?

Posted by rachel | 18 October 2015, 1:43 pmWe’re showing the Oresteia in Nottingham next spring if that’s any good to you – on Thursday 3rd March: Agamemnon in the afternoon and Libation-Bearers and Eumenides in the evening. Preliminary announcement of the season at http://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/argonautsandemperors/2015/08/12/greek-tragedy-on-the-small-screen/.

Lynn

Posted by Lynn Fotheringham | 19 October 2015, 4:33 pm