Earlier this week I wrote a post about Michael Barry’s memoir From the Palace to the Grove which details his life in television from 1938 to 1952. I lamented that he did not twin this revealing volume with a personal account of his later career – and that prompted me to pull from my shelf a handsome volume that, in part, is a commemoration of one of Barry’s greatest small-screen triumphs.

Earlier this week I wrote a post about Michael Barry’s memoir From the Palace to the Grove which details his life in television from 1938 to 1952. I lamented that he did not twin this revealing volume with a personal account of his later career – and that prompted me to pull from my shelf a handsome volume that, in part, is a commemoration of one of Barry’s greatest small-screen triumphs.

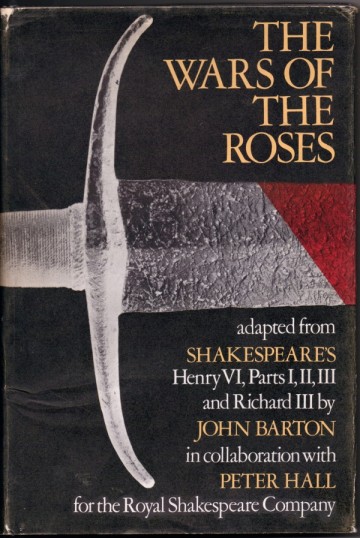

The Wars of the Roses by John Barton with Peter Hall (and some assistance from William Shakespeare) was published by the British Broadcasting Corporation in 1970. That date is rather odd since it is the script of an adaptation of four of Shakespeare’s History plays that was first seen in Stratford-upon-Avon in August 1963 and then shown in three parts on BBC Television on 8, 15 and 22 April 1965. Quite why it took five years from transmission for the book to appear is a mystery, although Peter Hall suggests that the company did not want the scripts published ‘while the production was still in our repertoire’ because

we wished it to be judged for what it communicated in performance, and we did not draw attention to the details of our alterations beyond acknowledging that they had been made. (‘Introduction’, The Wars of the Roses, London: BBC, pp. viii-ix; all further page references are from this volume)

The stage original, adapted – sometimes quite freely, by John Barton ‘in collaboration with Peter Hall’ (they also co-directed) – from the three parts of Henry VI and Richard III, remains one of the great triumphs of the Royal Shakespeare Company. When the trilogy first appeared, the company was only two years old and the vivid, urgent production did much to establish the new company. Michael Bakewell writes in the book that the BBC then questioned whether it should produce a television version when only four years earlier, in 1960, it had staged its own hugely successful version of the Histories, An Age of Kings (which also included Richard II, Henry IV parts 1 and 2 and Henry V).

The answer was that all of us [Bakewell writes] – the Head of Drama Group, Sydney Newman, Norman Rutherford, his Assistant, and myself – felt that the Royal Shakespeare’s (sic) production was so memorable and that the new version of the plays themselves […] was such a remarkable achievement that the whole work emerged in a totally new light and that we need have no fear of covering the same ground again. (‘The television production’, p. 231)

The book, which is gorgeously designed (I can’t find a credit) and cost 50 shillings (in those days just before Decimal Day, the price is also listed as £2.50), is mostly the full script of the three plays. Also included is an Introduction by Peter Hall, a section titled ‘The making of the adaptation’ by John Barton, a note of ‘The set’ by designer John Bury, and a cast and crew listing for the television version. What makes it invaluable for the television historian, however, not to mention producers and others interested in adapting Shakespeare for the screen, is Michael Bakewell’s five-page essay, ‘The television production’.

Michael Bakewell was Head of Plays at the time of the television version, and his thoughtful piece is an excellent account of decisions that any producer faces when considering how to make a screen version of a successful stage presentation.

Michael Bakewell was Head of Plays at the time of the television version, and his thoughtful piece is an excellent account of decisions that any producer faces when considering how to make a screen version of a successful stage presentation.

From the outset [he writes] all those concerned were intent on finding a new way of presenting Shakespeare on television. […] What was intended for The Wars of the Roses was to re-create a theatre production in television terms – not merely to observe it but to get to the heart of it […]

The possibility of moving the whole production into a studio was rejected at a very early stage. Although this would have given us total control from a television point of view, it was felt that the theatre for which the production had been designed played an essential part in the undertaking. (p. 231)

Central to the thinking about the theatre was Bury’s iron cage of a set across which characters dragged huge broadswords and grasped in desperation at metal grilles. Attempts to reproduce this in the studio would inevitably lesen its impact.

The solution seemed to be to convert the Royal Shakespeare Theatre into a television studio – to dispense with an audience and so to adapt the stage that our cameras could involve themselves as deeply as possible in the production […] What was needed at Stratford was to give the cameras exactly the kind of freedom and mobility they would enjoy in the theatre. (p. 232)

Half of the seats in the stalls were removed, the stage was extended out into the auditorium, and a platform was built across the stalls for cameras and sound booms to move on. One camera was lifted high above the stage, another placed in the orchestra pit ‘to give a kind of death’s eye view’, while a hand-held camera was also used in some of the battle scenes. (I have searched for photographs of the production process and have yet to find a single one – the RSC archives do not have any; if anyone knows of documentation of the process, I would love to hear about this.)

The logistical problem solved, the BBC then threw a team of 52 people at the production for eight weeks of shooting, with two directors (Michael Dews and Robin Midgeley) and producer Michael Barry. Bakewell details some of the key changes imposed by the television process, and he acknowledges that at times

the television production departed a long way from what was seen on stage at Stratford, but it conveyed overwhelmingly the feeling of the action. As in so many other moments in the operation it was found that the most successful way of conveying the spirit of the Hall and Barton production was not to imitate what they had done but to achieve the same aim by doing something that would prove much more effective in television terms. (p. 234)

You can get an idea of how this worked because the full production is (currently) available on YouTube (much of it from a rather good copy, even if the upload is undoubtedly illegal). Here is the first part:

I plan to write something more substantial about the production in the future. In the meantime, should you find yourself producing a television version of a Shakespeare staging can I recommend that you begin by reading Michael Bakewell’s essay.

Thanks for this great post! Back in the 1980s I remember Michael Billington being involved in making a documentary about Peggy Ashcroft. He was searching for footage, and had asked the BBC for The Wars of the Roses. He was told the films had been destroyed. In the mean time he came to the Shakespeare Centre Library where I worked, and where the RSC’s archives were kept to ask if a copy was in the archives, but it was not. It was only some time later after a fuller search that the BBC found the films. As soon as they were found the SCL asked the BBC to make a copy for the theatre’s archives, and I remember they were eye-wateringly expensive, but were thought to be worth it because of value and rarity of the film. Fortunately The Wars of the Roses have become widely available in recent years but it’s worth remembering how easily they could have been lost.

Posted by Sylvia Morris | 23 November 2012, 9:00 amHow fascinating, Sylvia – many thanks. It is a good thing that The Wars of the Roses circulates more widely now, albeit too often (as on YouTube) in poor quality versions. But there really, really needs to be a proper DVD release (and that’s something I’m trying to make happen). I don’t suppose you have ever come across any photos from the production process, have you?

Posted by John Wyver | 23 November 2012, 9:07 amWhen I read your comment about there being no pictures in the RSC’s archive it did ring a bell, but presumably you’ve already asked the SCLA to check the main files? I was intrigued to read the account about how they set up the auditorium for the filming and I’m pretty sure I’ve never seen pics of that. But I think I might have seen something, and will think about where! I can look up a few references, but not until the end of next week. Perhaps the local newspaper, or in a special feature: the National Geographic did a feature on the production, for instance. I’m assuming the filming took place during the winter of 1964-5, but do you know the exact dates?

Posted by Sylvia Morris | 23 November 2012, 10:37 amThat’s very intriguing – and, yes, I have asked SCLA to check the files – there is next-to-no documentation there. Anything further would be brilliant, and of course there is no rush on this. I do have the filming dates from the relevant production files at WAC, which I want to make the subject of future posts – but these are not immediately to hand. I will dig them out and contribute them here in the next few days. Thanks again.

Posted by John Wyver | 23 November 2012, 11:14 amI have extensive records and newspaper coverage of the filming in 1964. Some detail is in ‘A Band of Arrogant and United Heroes,’ Please email me – rbp@kes.net – and I will be happy to help.

Posted by RICHARD PEARSON | 7 December 2012, 8:38 amThat’s incredibly kind, Richard – and I’m delighted to be in touch. I have your book, which is enormously valuable. I’ll e-mail at the weekend and look forward to speaking.

Posted by John Wyver | 7 December 2012, 10:17 amI can’t help but feel that in 40 years’ time I shall be boring everyone in my old people’s home with memories of Michael Boyd’s Histories, and still bemoaning the fact that they were never filmed. Theatre-goers accept the ephemeral nature, and often rejoice in the variation in performance from one night to the next, but some productions are just too good to live only in the memory of a few dozens of thousand people (or far fewer in many cases).

Posted by Anna | 25 November 2012, 2:43 pmI know, I know, Anna – and maybe I’ev said before that at the BBC’s request I did an extensive development project to budget and schedule a television version of Michael Boy’d Histories. But I’m afraid that the plan got gazumped by Sam Mendes and The Hollow Crown – the BBC decided to proceed with that rather than working with the RSC on what ought to have been an eight-film cycle. So close, and yet…

Posted by John Wyver | 25 November 2012, 3:07 pmMy friend and I have a plan that if either of us wins millions on the lottery we’ll reconvene the entire ensemble, rebuild the Courtyard if necessary, and get it filmed. Which would give me far more satisfaction than the mansion and the sports car and the yacht to be perfectly honest.

Posted by Anna | 25 November 2012, 3:38 pmI know it’s not the same, but archive videos of both versions of the Boyd Histories (at the Swan and at the Courtyard) were made and are available for viewing at the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive in Stratford-upon-Avon. The Swan ones were filmed from both ends to ensure they caught all the action, but the tapes have not been edited in any way. Before anyone asks, the recordings are not to be copied, loaned or purchased.

Posted by Sylvia Morris | 6 December 2012, 2:48 pm