At 7.50pm on 31 July 1965, the Saturday-evening audience for BBC2 was treated to an hour of melodrama . . . melodrama, that is, as it had been played on the 19th-century stage. The production offered that evening, titled Maria Marten; or, The Murder in the Old Red Barn, was the first in a curious series of six melodramas, all with a theatrical pedigree, transmitted in a prime-time viewing slot under the banner Gaslight Theatre.

At 7.50pm on 31 July 1965, the Saturday-evening audience for BBC2 was treated to an hour of melodrama . . . melodrama, that is, as it had been played on the 19th-century stage. The production offered that evening, titled Maria Marten; or, The Murder in the Old Red Barn, was the first in a curious series of six melodramas, all with a theatrical pedigree, transmitted in a prime-time viewing slot under the banner Gaslight Theatre.

Maria Marten; or, The Murder in the Old Red Barn was an anonymous drama which – based on a real 1827 murder and execution – existed in several versions. The actor and theatrical manager Alec Clunes (1912-1970) adapted it for television, and also acted as advisor to the producer, Bryan Sears (1916-1999). This partnership was the model for the following five productions, suggesting that Sears and Clunes together may have had a role in devising the series for the BBC. Certainly, Clunes had produced at least one of these melodramas for the stage: follow this link for some photographic images of his 1952 production of Maria Marten at the Arts Theatre. Furthermore, as a nod to 19th-century theatrical practice, a small ‘resident company’ of actors – including Ronnie Barker, Leslie French, Eira Heath, Alfred Marks and Warren Mitchell – was formed to take the leading roles in these plays.

Maria Marten was followed in the five subsequent weeks by the following Saturday-evening Gaslight Theatre presentations on BBC2:

7 August 1965: Sweeney Todd; or The Demon Barber of Fleet Street by Charles Dibdin Pitt, which had first been staged in 1847 (in an adaptation which he adapted from the serialised story The String of Pearls before the serialisation had been completed!)

7 August 1965: Sweeney Todd; or The Demon Barber of Fleet Street by Charles Dibdin Pitt, which had first been staged in 1847 (in an adaptation which he adapted from the serialised story The String of Pearls before the serialisation had been completed!)

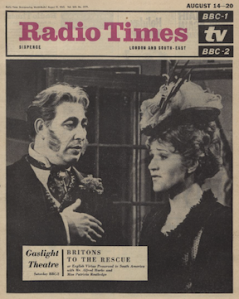

14 August 1965: Britons to the Rescue; or, English Virtue Preserved in South America was a television adaptation (by Alec Clunes) of Paul Meritt and Henry Pettitt’s British Born, a patriotic melodrama which had first been staged in 1873. The production starred Ronnie Barker and Patricia Routledge. (It was a theatre-heavy evening: later, BBC2’s Cinema 625 strand offered Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1957 The Witches of Salem, a film adaptation of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible.)

21 August 1965: The Blood-Craz’d Scourge of the Redskin Wilderness; or, What You Will was an adaptation of the 19th-century American revenge melodrama Nick of the Woods; or, the Jibbenainosay by Louisa H. Medina.

28 August 1965: The Drunkard; or, The Sins of the Parents Shall be Visited . . . was an adaptation for television of the 19th-century American melodrama The Drunkard; or, The Fallen Saved by W. H. Smith. As the title suggests, this was a temperance play. First produced in 1844, it was the most popular play in America for some years. (An Associated-Rediffusion production had been transmitted on ITV a decade earlier in 1955.)

4 September 1965: Walter Melville’s The Worst Woman in London, first staged in 1899, is a ‘wicked woman’ melodrama, telling of a woman’s manipulation of a man.

A lavish full-page article introduces the first production, and the series as a whole, in the Radio Times of 29 July 1965 (p. 4): ‘step back into the Victorian age and take a seat in the stalls’, encouraged the by-line of this article by Charles Fox. ‘Viewers will see the production just as the audience in the theatre did’, he concluded: ‘In fact the whole affair should be rather like an outside broadcast – but an outside broadcast from the last century’.

To get the audience in the mood, the Radio Times listing for each production was humorously written in the style of 19th-century melodrama, with puns and an emphasis on technological innovation: rather than the credit ‘Lighting by’ we have ‘The New Electric Lights were all man-handled by’, and rather than ‘Sound by’, we have ‘Acousticals were in the Sound hand of’, etc. It is noteworthy, I think, that each play-listing is accompanied, elsewhere in the magazine, by a large photograph and a few paragraphs on its performance history and how it came to be put on television, as a way, perhaps, of enticing the reluctant or uncertain viewer in.

I came across this series of plays for the first time yesterday, whilst doing data entry on the Screen Plays database. I’ve not yet had chance to check with the BBC whether, as is believed, the tapes of all these productions were wiped. I don’t yet know if production documentation on the series or the individual productions exists in the BBC’s archives. And I haven’t, owing to other commitments, even had time to scan the online newspaper databases to gauge the critical reception of these television productions.

Furthermore, quite what Charles Fox, the writer of the Radio Times article cited above, meant when he said ‘Viewers will see the production just as the audience in the theatre did’ baffled me. Until, that is, I came across a page or two on the Gaslight Theatre series in The Authorized Biography of Ronnie Barker by Bob McCabe (London: BBC Books, 2004), which offers a remarkable clue or two about how these television productions incorporated the ‘stage business’ of 19th-century melodrama. He narrates one of the very distinctive ways in which ‘Viewers [saw] the production just as the audience in the theatre did’ as follows:

They had models like they used to have in Victorian times. There was a chase across into the distance: the policeman chases this man off stage and further down on came these puppets that went across, then smaller puppets came across, and then tiny puppets came across. It was very funny. (p. 72)

Barker recalls how he was ‘supposed to be the manager of the company’, and since the manager was supposed to be playing the parts of both a man and his son in Maria Marten, at one point he had to do a costume and make-up change in thirty seconds flat (for the plays were, he recalls, being performed ‘as live’ in the BBC’s Television Theatre at Shepherd’s Bush). It is clear from the Radio Times listings for the six productions that it was not unusual for one actor to play up to three different (and sometimes cross-gender) parts, so frequent, and possibly hectic, changes of costume would have been the norm.

Barker recalls how he was ‘supposed to be the manager of the company’, and since the manager was supposed to be playing the parts of both a man and his son in Maria Marten, at one point he had to do a costume and make-up change in thirty seconds flat (for the plays were, he recalls, being performed ‘as live’ in the BBC’s Television Theatre at Shepherd’s Bush). It is clear from the Radio Times listings for the six productions that it was not unusual for one actor to play up to three different (and sometimes cross-gender) parts, so frequent, and possibly hectic, changes of costume would have been the norm.

The book also documents how Barker got involved in cutting the plays down so that they could play them within the hour’s slot. Although Clunes is throughout credited as the person who adapted the scripts, it looks like the ‘manager’ Ronnie Barker also had a hand in making them work comedically on television, an experience which, of course, prepared the way for writing comedy material later in his career.

A little more anecdote comes our way courtesy of Richard Webber’s Remembering Ronnie Barker (London: Arrow, 2011). In it, the actor Warren Mitchell, who played in several of the productions, notes that it was a ‘daft idea the BBC had of having a theatrical director and a television director trying to work hand-in-hand, and it didn’t work’. Eira Heath is quoted in agreement: ‘The television director and theatre director were so good in their own fields, but it didn’t quite work bringing them together’ (pp. 126-27).

A ‘daft idea’ it may have been, but one that certainly calls for some further research. I’m looking forward to finding out how some of the issues which may well have proved problematic for both the television practitioner and the viewer-at-home, such as the figure of the ‘wicked woman’ and the xenophobia-bordering-on-racism evident in some of these plays, were presented on television and received both by the critics writing in the press and the domestic audience.

Discussion

No comments yet.