This post takes as its focus the BBC Television transmission of a production of Sophocles’ tragedy Oedipus the King, directed by Richard Callanan, which starred Patrick Stewart in the title role and Rosalie Crutchley as Jocasta. This production was one of sixteen which were co-produced with The Open University to support the work of distance-learning students who were enrolled on its course A307 Drama. Since it was also transmitted on television it will also, of course, have reached a wider public audience in its annual transmissions over the five cycles of the year-long course’s life from 1977 (albeit one that happened to be watching BBC2 early on Sunday mornings). This blog post is another (small) chapter of my Greeks on Screen case study; but it also marks the first step of my second case study on stage plays produced on television in educational contexts.

The use of television in The Open University course A307 Drama

In 1977 The Open University launched an ambitious new course called A307 Drama, the aim of which was for students to develop a critical understanding and appreciation of drama both as literature and in performance. This second aim was supported by the television transmission of sixteen fifty-minute programmes: each of these was a production of (in most cases) part of one of the plays in the curriculum. The course resources also included ‘correspondence material’ (books and other papers sent to students through the post) and twenty programmes broadcast on BBC Radio (on such topics as ‘The Designer’, ‘Interpreting the Classics’ and ‘The Joint Stock and Mike Leigh’).

The Course Team who had constructed the curriculum for A307 were very much aware of the challenges involved in the use of television to encourage students to think about plays in performance on the stage; but it was also aware of the powerful potential of technology to overcome the financial and geographical hurdles which lay between some of its students and live theatre: ‘Television gives us the opportunity, which is at present unique in British universities, to present performances related to your critical study of play texts’. Accordingly, in the introductory material for the course, the team included a section on ‘Using Television in a Drama Course’, which discussed such issues as ‘translating’ the stage play to television, television’s dramatic language, the selective nature of the television camera and the process of editing the television production. One of the first radio programmes, which included contributions by Dennis Potter and David Jones, was also devoted to discussing the differences between the two media for drama, focusing on issues such as ‘the relative importance of words in the two media’, ‘the conventions of naturalism and documentary-type drama’, ‘the relationship with the audience’ and ‘adaptation of stage plays to television’ (sources: ‘A Guide to the Course’, by Brian Stone and Beverley Stern, 1977, and ‘Supplementary Material A307’, 1977, The Open University Archives).

The television productions were also considered to be important in another way, as noted in the course’s ‘Broadcast and Assignment Calendar’: ‘the television programmes must provide the “pace-maker” for your study year. For it is crucial to keep your work on the set plays and your study of the correspondence material synchronised with the television broadcasts; should you lose step with the broadcasts, it means you will be falling behind’.

The plays chosen for study in the course were, it is said, ‘chosen for their importance in European drama’, an ambition which is interestingly reflected in the sub-set of sixteen plays selected for television production: Sophocles, Oedipus the King; William Shakespeare, Macbeth; The York Crucifixion and The Brome Abraham and Isaac; Carlo Goldoni, The Venetian Twins; William Congreve, The Way of the World; Alfred Jarry, Ubu Roi; Georg Büchner, Woyzeck; Henrik Ibsen, Peer Gynt; Henrik Ibsen, The Wild Duck; Anton Chekhov, Three Sisters; August Strindberg, The Ghost Sonata; Luigi Pirandello, Six Characters in Search of an Author; Bertolt Brecht, The Exception and the Rule; Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot; Jean Genet, The Balcony; Athol Fugard, Sizwe Bansi is Dead (n.b. this last one was an existing 1972 BBC TV production).

I hope to discuss some of these productions in future blog posts. There are certainly some interesting stories to be told: for example, the argument that took place between The Open University and the BBC over the production of Genet’s The Balcony. First, the transmission was moved from Sunday to Saturday, so as not to offend, but then the higher echelons of the BBC, on discovering the nature of some scenes in the play, which is set in a brothel, demanded substantial cuts which The Open University refused (Sue Reid, ‘BBC Wants Scenes Cut from Open University Play’, The Times, 14 May 1977, p. 16).

The broad(-er)casting mission of The Open University

When placing these (albeit in most cases partial) play productions within the wider history of stage plays on British television, it is worth recalling the mission of The Open University to serve the general public as well as its paid-up students:

TV and Radio programmes have always been an important way of increasing the University’s recognition, enhancing its reputation and fulfilling its mission ‘to promote the educational well-being of the community generally’. (‘Small Screen Heroes: The OU and the BBC’, online at http://www8.open.ac.uk/researchprojects/historyofou/story/small-screen-heroes-the-ou-and-the-bbc)

With this in mind, it is fascinating to discover that in 1977 — the first year of the course — the BBC published a book in association with these televised productions, titled Sophocles to Fugard, written by Brian Stone (the chairman of the course team; founder member of The Open University where he was Reader in English Literature) and Pat Scorer (a tutor on the course; later, from 1985, his wife). In their introduction, they make clear in the first line that the book is written for ‘the interested viewing public’. A mailing to The Open University students more explicitly defines this audience:

With this in mind, it is fascinating to discover that in 1977 — the first year of the course — the BBC published a book in association with these televised productions, titled Sophocles to Fugard, written by Brian Stone (the chairman of the course team; founder member of The Open University where he was Reader in English Literature) and Pat Scorer (a tutor on the course; later, from 1985, his wife). In their introduction, they make clear in the first line that the book is written for ‘the interested viewing public’. A mailing to The Open University students more explicitly defines this audience:

Sophocles to Fugard is not part of the course material; it is written to introduce the series of television programmes to the general public, and to students of drama at any level who might be using the programmes outside the Open University system […] it offers a view of the play based on the television performance itself. (‘A307 Mailing 1, 1981’, Open University Archives)

The book’s Introduction goes on to discuss television, which it considers to be ‘now the chief drama medium in the world’, ‘as electronic artefact’. It makes the important point that — at the time of writing, in 1977 — ‘Television drama suffers extraordinarily if the set is a bad one or is not tuned properly―you cannot see the detail of the faces, the colours are wrong, there are ghost lines round outlines, or blurs, or sudden contrast changes’ (p. 10). It goes on to explain the practicalities of putting together a production of a play for television, from the technical and artistic team, to the nature of the different kinds of camera shot and the aesthetics of camera-cutting. Interestingly, the Introduction concludes with the observation that ‘This drama series made demands on all staff―production, design, costume, make-up, camera, sound and special effects among them―beyond any other series of programmes made for the Open University’ (p. 11).

The plays were produced in the relatively small (26×64 feet) Studio A at Alexandra Palace, London, where — since 1969 (when The Open University was established) — there was a BBC production department specially for the making of Open University programmes (until 1980-81 when The Open University relocated to Milton Keynes). Budgets were modest and ‘our set designs were planned to be functional and economic’ (‘A307 Supplementary Material A307’, 1977, The Open University Archives). There were four cameras, one of which was mounted on a scaffold which raised the lens to about ten feet high. (See the TV Studio History website for photographs of Studio A in this period.)

See the studio plan, adjacent, for how the cameras and the set design made the most of the small space for the production of Oedipus the King, which includes a small circular acting space, a walkway from this to the palace door, with some space around the central acting space for the chorus to dance. This space is bordered by rocks and small trees, and illuminated sky-blue ‘walls’ give a pretty good impression of an outdoor setting (apart from the occasional shadows cast on them by the chorus).

Oedipus the King

The first play, and the only Greek play, in the series of television productions was a shortened version of Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus under the title Oedipus the King (and referred to often in the course notes as Oedipus the Dictator). The second half of the play (from line 769 to the end) was performed, in the translation of John Ferguson, a classicist and Dean of the Arts Faculty.

The didactic purpose of this presentation meant that this was no modern updating of the Sophoclean play; rather, the text is given in the full and close translation of the original Greek, the actors wear half-masks and wigs, the set consists of a small circular acting space before a large palace door, and the costumes evoke an unspecific ‘other’ time and place, somewhat suggestive of ancient Greece.

The programme opens with the image of a bust of Sophocles which serves as the visual anchor for an introductory minute or two of information about the original play, when and where it was first performed, and a note on the present production which, it is said, ‘does not seek to be an archaeological copy of the original performance, but it does put primary emphasis on word, movement and gesture, within the medium of television’; this sequence closes with some words with a sentence summarizing the action of the play thus far.

Brief captions, introducing the play and the translator, then appear over a static image of the set with the Chorus, Oedipus and Jocasta. The production opens at this point, when Oedipus, king of Thebes, tells his wife Jocasta that he is anxious about the old prophecy of parricide and incest (at this point he mistakenly thinks that the parents who reared him are his biological family, oblivious of the fact that his wife Jocasta is, in fact, also his mother, and that the parricide has already taken place some years ago).

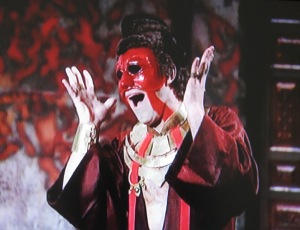

In the image on the right, Oedipus (Patrick Stewart), at the end of his opening speech, prays at the altar that the prophecy will not come to pass. Here, the half-masks can clearly be seen in their pearly, indeed shiny, luminescence. All of the cast wear wigs which, in close-up, look as if they have been knitted (and Oedipus’ wig has a distinctive Mohican shape). The wide sleeves and crossover at the chest of the chorus’ garments evoke Japanese kimono, whilst the richer colour and elaborate ornamentation of Oedipus’ costume effectively suggests his kingly status.

The acting is interesting: the parts are played in a rather solid way, without an excess of verbal emotion or, it seemed to me, the actors’ personal interpretation of the parts, almost as if they are engaged in an attempt to serve as a conduit for the text rather than actually inhabit the characters.

In fact, as with the costumes, there is a significant degree of stylization in the acting by both the main characters and also the chorus. At the moments of greatest intensity — for example, when Jocasta exits the stage for the last time, entering the palace (backwards, with her arms raised around her head) where she will commit suicide, and also when Oedipus emerges from the palace newly self-blinded (see adjacent image) — the actors appear with mouths gaping for a few seconds, but without emitting much, if any, sound. The effect is reminiscent of Edvard Munch’s ‘Skrik’ (‘The Scream’) series of paintings.

The entirely male six-strong chorus is composed of two speakers (Derek Godfrey, Joe Melia) and four dancers (Nick Burge, Nicholas Carroll, Kenneth Mason, Hugh Spight), although physically they appear as a homogenous group throughout. The movement, choreographed by Jonathan Taylor, is worked out in bold, expansive gestures and strong poses, made together or in quick succession. The pattern is for one of the speakers to deliver the lines, framed visually by the other chorus members who strike poses around him, to a background of music scored for various woodwind instruments and drums and harp. This bold and sometimes surprising presentation of the chorus is visually arresting and the frequent changes in pose kept this viewer, at least, engaged throughout.

I’m really looking forward to seeing how the rest of the series unfolds and also to diving into the reading list I’m beginning to compile on the use of television in educational settings.

(Photographs © The Open University)

One of the fascinating aspects of these dramas is that they were recorded in the studio at Alexandra Palace from which the pre-war pioneers began broadcasting live dramas in the late 1930s. The studio plan above (which is worth clicking on to reveal the details) is pretty much the plan that would have been used for hundreds of live dramas from 1936 on.

Remarkably, although access to it is very restricted, Studio A today is still pretty much exactly as it was pre-war and when the OU was working there. I hope you can find out more about the production process, Amanda – how long was the rehearsal process, how many hours did the team have in the studio and so forth? Those details too will make a really interesting comparison with the earliest live dramas.

Posted by John Wyver | 2 September 2011, 4:53 amThanks for these valuable comments and questions, John! I very much hope to discover more on the production process as my research progresses … watch this space!

Posted by Amanda Wrigley | 2 September 2011, 7:38 amAfter reading this I was inspired to post about this play here. http://www.open.ac.uk/blogs/History-of-the-OU/?p=1665 and I’ve put up something about the book ‘Sophocles to Fugard’, here http://www.open.ac.uk/blogs/History-of-the-OU/?p=1732

Posted by Dan Weinbren | 12 September 2011, 6:52 pmMost of the history of A307 can be filled in by the surviving producers, including Nancy Thomas who was Executive Producer Arts at the BBC Open University Production Centre. Our memories may be fading, but i suspect much that is pertinent about the Series is deeply burnt into our minds! The repository of the as yet not fully undisclosed history of The Balcony controversy is Robert Rowland, retired and venerable then Head of OUPC . I produced four of the plays including The Balcony.

Posted by Nick Levinson | 11 November 2011, 5:50 pmNick, thank you so much for getting in touch! We are absolutely delighted to hear from you: your name is high on the list of those we would love to talk to about this series of productions. As you suggest, you would be able to tell us much of importance. If I may, I’ll get in touch with you over the email address you have supplied.

Posted by Amanda Wrigley | 12 November 2011, 7:23 amIs it common in the UK for education and TV to be linked like this?

I found the discussion of the style to be particularly fascinating for the way that the piece tried to both educate and entertain. It is an instructive example of how a production can try to position itself between presenting the formal attributes of the source material and doing so within a popular medium. I will definitely mention it to my class!

Posted by Robert Davis | 27 November 2011, 2:50 pmThanks so much for your thoughts, Robert — it’s good to hear how this strikes you. Yes, the Open University has a long history of broadcasting its audiovisual teaching material on television (usually very early in the morning!) and still today (when DVDs are rather sent out to their distance-learning students) they work with others producers on usually fascinating television projects not directly linked with the courses they teach. There is also, of course, the history of television programmes ‘for schools’ which is something I don’t yet know much about but it forms part of my next case study, alongside further exploration of the drama output of the Open University / BBC relationship.

Posted by Amanda Wrigley | 1 December 2011, 9:25 amHello, I reviewed both this and King Oedipus from last night’s screening on my blog:

http://loureviews.wordpress.com/2012/06/08/archive-tv-review-greek-tragedy-on-the-small-screen-1-bfi-southbank/

Posted by Louise | 8 June 2012, 4:53 pmWhy is there no video of this performance available on this site or anywhere else on line?

Posted by Alex | 21 November 2015, 9:50 amI’m afraid that rights restrictions prevent the circulation of much early television including this production.

Posted by John Wyver | 21 November 2015, 1:39 pmwhat ever happened to bbc radio’s 195? production of w.b.yeats’s version?

Posted by Brian Burden | 18 August 2018, 1:26 pm