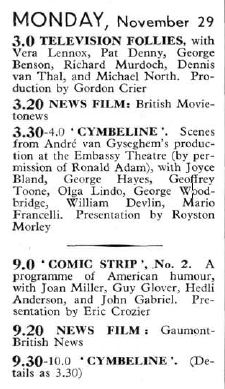

This long-promised post complements two previous ones (here and here) in which I sketched the background to two early television presentations of scenes from William Shakespeare’s Cymbeline. A November 1937 live broadcast from a studio at Alexandra Palace featured extracts from Andre van Gyseghem’s production then running at the Embassy Theatre. Nineteen years later, in October 1956, two scenes from the recently opened Old Vic production by Michael Benthall were transmitted live from the Lime Grove studios.

The fragments featured in 1956 — Iachimo attempting to woo Imogen in Act 1 Scene 6 and the ‘trunk scene’ that is Act II Scene 2 — were also given (along with other scenes) in 1937 and, remarkably, detailed camera scripts for both productions have been preserved in the programme file T5/121 in the BBC Written Archives Centre. (No recording exists of either production.)

The scripts permit the comparison between the basic language of studio drama, at least as employed in this production, just a year after the start of the BBC Television Service, and the relative sophistication of that language two decades on. As far as I know, no such comparison has been previously attempted, and Cymbeline may be unique as a drama for which pre-war and post-war camera scripts exist.

In the studio in 1937

Act I Scene 6 of Cymbeline begins with Imogen, alone on stage, unhappy at the banishment to Rome of her husband Leonatus by ‘a father cruel and a stepdame false’. Iachimo is announced — in the original text and in the 1937 script by the servant Pisanio, although in the 1956 scenes by Imogen’s maid. Iachimo brings news from Rome, but he has really come to seduce Imogen, which he has made a bet with Leonatus that he will be able to do. There follows a lengthy exchange between the two main characters that lasts for 223 lines (The RSC Shakespeare, ed. Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen, Basingstoke: MacMillan, 2007, pp. 2256-2261). Imogen resists all the wiles of Iachimo, but as a kindness to this supposed friend of her husband she agrees to store his trunk overnight.

Three cameras were employed for the 1937 studio broadcast, while four were used in 1956. But almost the whole of this attempted wooing of Imogen was played on camera 1. Only after 148 lines in the camera script is there a mix to camera 2, when Imogen calls out for Pisanio to rescue her from Iachimo’s increasingly ardent approaches. (Studio technology in 1937 could not achieve direct cuts between cameras; mixes might have taken between two and four seconds to change from one shot to the next.) Just nine lines are played on camera 2, and then there is a mix back to camera 1, which is used to cover the remainder of the scene.

Three cameras were employed for the 1937 studio broadcast, while four were used in 1956. But almost the whole of this attempted wooing of Imogen was played on camera 1. Only after 148 lines in the camera script is there a mix to camera 2, when Imogen calls out for Pisanio to rescue her from Iachimo’s increasingly ardent approaches. (Studio technology in 1937 could not achieve direct cuts between cameras; mixes might have taken between two and four seconds to change from one shot to the next.) Just nine lines are played on camera 2, and then there is a mix back to camera 1, which is used to cover the remainder of the scene.

It is unlikely that the shot from camera 1 would have been entirely static for all of the 214 lines which it was used to cover. But the studio Emitron cameras at this time had only a single, fixed lens (so it was not possible to change shot by zooming), and those that were mounted on trucks (as presumably camera 1 was) were capable of only moderate tracking in and out. It is possible, of course, that the studio director improvised on the night and included other shots — but the fact that the camera script features only one change indicates something of the expectations of studio drama one year after the opening of Alexandra Palace.

The other extract played both in 1937 and 1956 was the ‘trunk scene’ of Act II Scene 2, in which Imogen retires to bed and Iachimo emerges from the trunk to stare lasciviously at her sleeping body and to steal her bracelet. The comparatively short scene of 53 lines features a 41 line speech by Iachimo. In the 1937 script the scene begins on a wide shot from camera 2 over which is superimposed a shot of the trunk from camera 1. This fades out and the action begins on camera 2 alone. After twelve lines the script indicates a mix to camera 1 for Iachimo emerging from the trunk. After just two lines the shot mixes to camera 2 for most of Iachimo’s speech before returning to camera 1 as he goes back to the trunk at the close. In less than one quarter of the length of the previous scene, there are four shot changes, two more than in the whole of the wooing exchange.

Fast forward to 1956

By the time the BBC came to present scenes from Cymbeline again, in October 1956, studio drama had developed significantly during twelve years of productions. (The Television Service closed because of the war from September 1939 to July 1946.) The main base of operations had shifted to Lime Grove, with the Cymbeline extracts being broadcast from Studio D. The cameras now had turret lenses, with a choice of three shot sizes from each position, and they were also significantly more mobile. For Cymbeline, one was mounted on a Mole Richardson crane and two others on motorised ‘Vintens’, which facilitated rapid movement around the studio floor in all directions.

The text of the two scenes is much as in 1937, although some ten lines or so from Act I Scene 6 have been cut from the later production. But the screen language is far more complex. In the wooing exchange there are now thirty-one shot changes, while in the shorter trunk scene there are seventeen. All of these are now hard cuts.

The change can be seen immediately in the treatment of Iachimo’s introduction to Imogen, all of which in 1937 was presented as just part of the lengthy first shot from camera 1. Imogen’s maid Helen says that Iachimo has come from Rome, after which there is a shot without dialogue described in the script in this way:

Deep 3-sh [shot with three people in frame] across IACHIMO LFG [left foreground] to HELEN/IMOGEN

Hold as IMOGEN walks twds cam [towards camera]

HELEN crosses out of frame r [right]

2-sh IACHIMO/IMOGEN.

Before Iachimo speaks, the screen cuts to a medium-shot of him, and as he presents the letter from Leonatus, the script reads ‘Pan him right to IMOGEN. 2-sh IACHIMO/IMOGEN.’ As Imogen responds there is a cut to a third camera, which presents a medium close-up of her. There is then another dialogue-free shot:

2-sh IACHIMO/IMOGEN

Hold 2-sh as IMOGEN walks into RFG

IACHIMO crosses to r of frame

Hold 2-sh

There have been four changes of shot so far, for just five lines of dialogue.

The instructions in the 1956 camera script are sufficiently detailed to allow a visual reconstruction of the scenes, and they reveal much of interest about the way in which studio drama worked at the time (although this detail is perhaps best presented in a journal article rather than a blog post). For the most part it is clear that shots present the person who is speaking, or very often both the speaker and the person being addressed in a two-shot. But occasionally there are variations. Midway through the wooing, Iachimo declares his passion for Imogen, with the following words:

Had I this cheek

To bathe my lips upon: this hand, whose touch

Whose every touch would force the feeler’s soul

To th’oath of loyalty: this object which

Takes prisoner the wild motion of my eye…

At ‘object’ the shot, which has been a close two-shot of both figures, cuts to a close-up of Imogen, and remains focussed solely on her for the remaining ten lines of Iachimo’s speech.

At the end of the wooing scene, after Imogen has agreed to look after Iachimo’s trunk, the action is enhanced by the use of the studio crane. In a two-shot (on camera 2) Imogen says to Iachimo, ‘You’re very welcome,’ and walks away from the camera as the shot is held. Cut then to a dialogue-free medium close-up (camera 3) of Iachimo, quickly followed by another cut to camera 1. This is how the script then describes the screen image:

Very high long shot of floor pattern

IACHIMO left of frame

Hold shot as he moves away from cam.

Two servants enter left of frame with trunk. 3-sh

Crane down fast and track in to let trunk pass in bottom foreground of frame.

Hold IACHIMO centre

Servants and trunk leave frame r.

As soon as they leave frame

TRACK IN fast to CU [close-up] IACHIMO

The focus on the trunk rendered in 1937 with a simple superimposition is achieved here with a comparatively elaborate crane and tracking move.

‘To the trunk again…’

Iachimo’s speech over the sleeping Imogen has been described as an ‘astonishing, voyeuristic episode […] which it can be both gripping and unsettling to participate in’. (Tony Tanner, Prefaces to Shakespeare, London: Belknap Press, 2010, p. 740). Television producer Michael Elliott certainly attempted to use the resources of his studio set-up to bring drama to the scene. After Imogen has fallen asleep, the script describes the shot in which Iachimo slips the bolt from the inside and emerges from the trunk (pictured above, in a production still from The Listener):

High MCU IMOGEN craned left.

Pan right to trunk

Crane r and down and pan l to pivot round trunk.

End shot with trunk bottom RFG and IMOGEN LBG. Crane up as IACHIMO comes out of trunk to hold 2-sh.

As the scene unfolds, on several occasions the camera pans down from Iachimo’s face to the prone Imogen and then back up to him. There is perhaps the suggestion here of his (symbolic) violation, as there is in the frequent use of high two-shots of the pair (from camera 1 on the crane). At the close, the opening crane shot is repeated as Iachimo returns to the trunk and slides the bolt to lock himself in. This section of the script ends with the instruction, ‘LOSE FOCUS’.

The analysis of the screen grammar of early studio drama is still very much in its infancy, especially when compared with the rich work of scholars such as David Bordwell, Janet Staiger and Kristin Thompson (notably in The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style & Mode of Production to 1960, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1985), Barry Salt, Ben Brewster and many others, with early film. But perhaps questions can begin to be asked here as a focus for further research. Expressed very crudely, a key shift can be identified in the years around 1910 from a ‘tableau’ style dominated by lengthy long-shots to one in which editing editing, close-ups, cross-cutting and scene dissection develop to construct a film’s narrative. To what extent is the emergence of the screen language apparent in the 1956 scenes from Cymbeline parallel to that of early film – and, crucially, what differences might be identified, associated with the very different social and cultural contexts in which television developed, its completely distinct relationship with its audiences, the radically different technologies and forth?

Thanks for this post! How interesting that Cymbeline was chosen (twice) for this treatment, being a relatively unpopular play, but I can see how attractive it was to get these scenes in close-up. I’m slightly surprised that they were seen as suitable for broadcast on the new medium of TV, as the trunk scene is quite erotic, and almost shockingly intimate.

Posted by Sylvia Morris | 9 January 2012, 10:12 am